Edited by Jeffrey T. Richelson/

Posted – September 4, 2013

On August 12, 2013, President Barack Obama announced (

Document 118) the impending creation of a group to review U.S. signals intelligence capabilities and communications technologies. Its mandate would be to "assess whether, in light of advancements in communications technologies, the United States employs its technical collection capabilities in a manner that optimally protects our national security and advances our foreign policy while appropriately accounting for other policy considerations, such as the risk of unauthorized disclosure and our need to maintain the public trust." That same day, Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper, Jr. announced (

Document 119) that he would be establishing the review group and its final report would be due no later than December 15, 2013.

The catalyst for the president's announcement was an unexpected event that occurred just a little over two months previously. On June 5, a British newspaper, The Guardian, began publishing a series of articles disclosing highly classified aspects of, and documents about, certain National Security Agency (NSA) electronic surveillance operations involving not only extensive collection of foreign communications, including Internet traffic, but the collection of the metadata associated with phone calls (foreign and domestic) made by United States citizens. A few days later, The Guardian revealed its source to be Edward J. Snowden, a former CIA employee who had been working at a NSA facility in Hawaii as an employee of Booz Allen Hamilton.

On June 14, the United States filed a sealed criminal complaint against Snowden, releasing only one page (

Document 74) to the public. Subsequently, Snowden departed Hong Kong, where he had been staying for the previous month (reportedly spending his final two days at the Russian consulate

[1]), using a SAFEPASS (

Document 83) issued by the Ecuadoran embassy in London. He arrived at Moscow's Sheremetyevo airport while seeking asylum elsewhere. While in Russia, he issued several statements (

Document 97). During that time, the United States sought to discourage nations offering Snowden asylum and pre-emptively requested his extradition (

Document 81) from at least one nation.

Snowden's potential movements also became the subject of a letter (

Document 91) from his father's lawyer to Attorney General Eric Holder asking for three guarantees to encourage his son to return home, including that he would not be detained or imprisoned prior to trial. Subsequently, in response to reported claims that Snowden feared being tortured if he returned, Holder wrote (

Document 105) to the Russian Minister of Justice, assuring him that Snowden would not be tortured or face the death penalty if he returned (or was returned) to the United States.

Director of National Intelligence James Clapper (Photo: ODNI)

The controversy that has erupted over Snowden and his disclosures is not the first time NSA has been at the center of controversy. In the 1970s, through leaks, investigative reporting, and congressional inquiries, the public learned of projects SHAMROCK and MINARET. The SHAMROCK program (1945-1975) involved several U.S. companies turning over the telegraphic communications that passed over their networks. Project MINARET "was essentially the NSA's watch list" and "used existing SIGINT accesses" to search for "terms, names, and references associated with certain American citizens." While MINARET officially began in 1969, the watch list activity had started at least as early as 1960, and did not originally involve American citizens. In 1975,

The Washington Post reported that the watch list had included prominent anti-Vietnam war activists such as Jane Fonda and Benjamin Spock.

[2]

In the 1990s, major concern arose — more overseas than in the United States — about a program designated ECHELON. That program involved the installation of software at a select number of "COMSAT Intercept" sites operated by what are today designated the "FIVE EYES" nations — the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The sites intercepted the traffic flowing through communications satellites and the ECHELON software sorted through it (particularly printed fax transmissions), routing those containing pre-selected key words to analysts in whatever FIVE EYES nation had expressed interest. However, claims that ECHELON was a far more extensive global surveillance operation produced an international controversy and a European Parliament investigation.

[3]

Perhaps the controversy around ECHELON would have had a significantly longer life had it not been for the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. But those events presaged the more recent controversies. In May 2006,

USA Today published an article titled "NSA Has Massive Database on Americans' Phone Calls: 3 Telecoms Help Government Collect Billions of Domestic Records."

[4] One lawsuit that followed was based on the claims of an AT&T employee (

Document 11) concerning a special room containing surveillance equipment at an AT&T San Francisco facility.

However, there was a lack of official acknowledgment or leaked documents to support the claims. Thus, an August 2007 Congressional Research Service examination of the issue (

Document 15) noted that "the factual information available in the public domain with respect to any such alleged program is limited and in some instances inconsistent, and the application, if at all, of any possible relevant statutory provisions to any such program is likely a very fact specific inquiry." The CRS study also stated that "It is possible that any information provided to the NSA from the telephone service providers was provided in response to a request for information, not founded on a statutory basis."

[5]

National Security Agency headquarters (Photo: National Security Agency)

In contrast, the pre-August 12 disclosures in

The Guardian, as well in

The Washington Post and the Brazilian media, were based on a variety of document sources. Further, the online stories provided links to many of the key leaked documents, including an inspector general's report on the STELLARWIND Program (

Document 23) — also known as the President's Surveillance Program (

Document 24) — as well as Top Secret documents specifying procedures concerned with targeting (

Document 25) and the 'minimization of data' about U.S. persons (

Document 26). Also appearing on the web were selected slides from a 41-slide presentation (

Document 55) on a program referred to as PRISM — involving the collection of Internet traffic from a variety of service providers — as well as a presentation on XKEYSCORE (

Document 18), which sorts through intercepted traffic.

Along with the PRISM revelations, charges that the U.S. had bugged the facilities of European governments produced the greatest reaction in Europe — and the announcement (

Document 95) of an investigation. However, the focus in the United States revolved around two programs, the Section 215 Bulk Collection Program and the 'PRISM' program, the latter based on Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 Amendments Act (

Document 20).

Among the first documents

The Guardian disclosed was a 4-page Top Secret 'Secondary Order' (

Document 59) from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) that commanded Verizon Business Network Services to provide an electronic copy of two 'tangible' things: "all call detail records or 'telephony metadata' created by Verizon for (i) communications between the United States and abroad; or (ii) wholly within the United States." The government subsequently released a heavily redacted version of the Primary Order (

Document 58) from the surveillance court.

The leak of documents concerning the Bulk Collection program had a number of consequences leading up to the review ordered by President Obama. The leaks provided new data on the evolution of the program (

Document 12,

Document 17), reporting to Congress (

Document 28,

Document 32), challenges by Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR) and others to the legal interpretations employed to justify the program (

Document 10,

Document 34,

Document 63,

Document 90a), as well as official reaction to those challenges (

Document 37,

Document 90b). The leaks also resulted in attempts by the government (

Document 79,

Document 92) to provide public reassurance — both with regard to the legality and utility of the program — including a single-spaced 22-page white paper (

Document 115). Labeled "Administration White Paper" and lacking any specific agency source, the document seems to include the kind of legal language and justifications that would likely appear in the still-Secret Office of Legal Counsel opinions describing the government's legal bases for the programs. Such attempts also met with rebuttals (

Document 68) by those less convinced of the utility of the Bulk Collection effort.

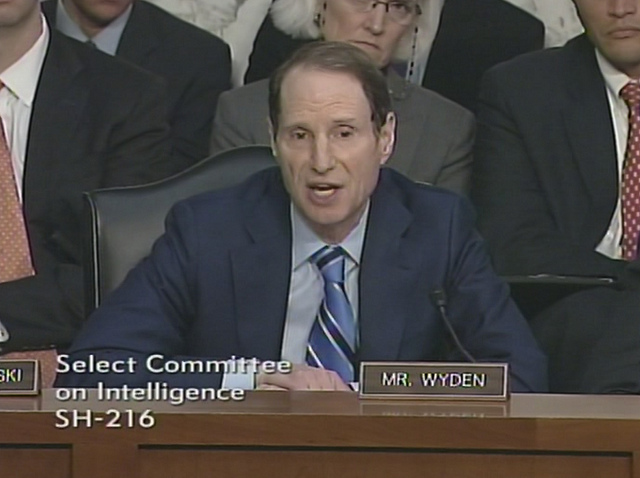

Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) (Photo: www.wyden.senate.gov)

Because of the leaks, DNI James Clapper had to provide various explanations (

Document 71,

Document 82) for his "no" response to a question Wyden had posed to him at a public hearing in March. Wyden had inquired whether the NSA collected "any kind of data at all" on millions or hundreds of millions of Americans.

In addition, there were amendments introduced in Congress that would have terminated the program — including Sen. Rand Paul's (R-KY) "Fourth Amendment Restoration Act" (

Document 67) and an amendment (

Document 101) by Representatives Justin Amash (R-MI) and John Conyers (D-MI) that would have prohibited funding for execution of any FISA order that did not limit collection to data that pertained to an individual who was the subject of an investigation. Objections to the amendment, which was ultimately defeated by the unexpectedly close margin of 217-205, came from Senate Select Committee on Intelligence chairman Dianne Feinstein (

Document 106), the White House (

Document 107), and DNI Clapper (

Document 108).

The contrast between the Bulk Collection program and the Section 702 'PRISM' program was that there was little dispute that the latter had produced significant intelligence that could be employed in operations against terrorist activities. Still, disclosure of the program was accompanied by the publication of relevant, sometimes Top Secret, documents (

Document 18,

Document 25,

Document 26,

Document 55) that produced significant controversy. One element of controversy concerned the specifics of the involvement of key communications providers (e.g. Yahoo, Google, Facebook) in the program — particularly if NSA had direct access to their servers.

National Security Agency director Gen. Keith B. Alexander (Photo: National Security Agency)

A second source of controversy concerned a number of NSA claims made in a fact sheet it had posted on the Web about the 702 program (

Document 78). The fact sheet sparked a letter from Senators Wyden and Udall (D-CO) (

Document 85) to NSA director Keith Alexander with two objections. The senators wrote to dispute what they considered "an inaccurate statement about how section 702 authority has been interpreted by the U.S. government." In addition, they objected to the statement in the fact sheet that any inadvertently acquired communication concerning a U.S. person that was not relevant to the purpose of the intercept, or evidence of a crime, had to be promptly destroyed. They characterized the statement as "somewhat misleading in that it implies that the NSA had the ability to determine how many American communications it has collected under section 702, or that the law does not allow NSA to deliberately search for the records of particular Americans." In his response (

Document 87), Alexander noted that "the fact sheet ... could have more precisely described the requirements for collection under Section 702." Shortly thereafter, the NSA removed both the Section 215 and Section 702 fact sheets from its website.

A number of disclosures and declassifications occurred subsequent to the president's August 12 announcement — primarily from

The Washington Post and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Among the documents provided by Snowden to the

Post was a Top Secret report (

Document 44) on the Washington-based activities of the NSA's Signals Intelligence Directorate, with collection limitations imposed by Executive Order 12333, the FISA, and other regulations. Over the course of a year starting April 2011, it noted 2,776 incidents (2,057 related to the executive order and 719 with regard to FISA). The report attributed the incidents mostly to "roamers" (foreign targets that entered the United States), but they also involved cases of a lack of proper FISC authority, database queries, errors in tasking or detasking, and collection at international transit switches. The

Post also first disclosed a 4-page document (

Document 125) titled "Targeting Rationale," which focused on what information should, and should not, be provided to FISA Amendments Act "overseers."

On August 21, 2013, the Office of the DNI declassified a collection of relevant documents with Clapper providing an overview in a release letter (

Document 123). Included in the documents were a directive on minimization (

Document 38) — which was a more recent version of one of the documents that first appeared in

The Guardian (

Document 26) — as well as testimony before closed Congressional hearings (

Document 41) and a semiannual compliance report (

Document 113). In addition, there were three 2011-2012 opinions (

Document 35,

Document 40,

Document 48) from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. The first of the opinions had been the subject of a lawsuit by the Electronic Frontier Foundation. It noted that "one aspect of the proposed collection — the 'upstream collection' of Internet transactions — is in some respects, deficient on statutory and constitutional grounds." The subsequent opinions (

Document 40,

Document 48) discussed the adequacy of the government's response to the court's criticism.

Compliance violations had been noted several days before the release in a press briefing (

Document 120) by John DeLong, NSA's director of compliance. His disclosures produced reactions from Senate intelligence chairman Feinstein and committee members Wyden and Udall. Feinstein stated (

Document 122) that her committee had "never identified an instance in which the NSA has intentionally abused its authority to conduct surveillance for inappropriate purposes," while Wyden and Udall wrote (

Document 121) that "we believe Americans should know that this confirmation is just the tip of a larger iceberg."

![NEOCASTRISMO [Hacer click en la imagen]](http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_5jy0SZhMlaU/SsuPVOlq2NI/AAAAAAAAH1E/4xt2Bwd2reE/S150/ppo+saturno+jugando+con+sus+hijos.jpg)