|

| In this Nov. 11, 1989, photo, East German border guards are seen through

a gap in the Berlin wall after demonstrators pulled down a segment of

it at Brandenburg gate. (LIONEL CIRONNEAU/Associated Press) |

Documents show accident and contingency, anxiety in world capitals

East German crowds led the way, with help from Communist fumbles,

self-fulfilling TV coverage, Hungarian reformers, Czechoslovak

pressure, and Gorbachev's non-violence

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 490

Posted November 9, 2014

For more information contact:

Thomas Blanton and Svetlana Savranskaya - 202/994-7000,

nsarchiv@gwu.edu

----------------

Washington, DC, November 9, 2014 –

The

iconic fall of the Berlin Wall 25 years ago today shocked international

leaders from Washington to Moscow, London to Warsaw, as East German

crowds

took advantage of Communist Party fumbles to break down the Cold War's

most symbolic barrier, according to formerly secret documents from

Soviet, German,

U.S., Czechoslovak and Hungarian files posted today by the National

Security Archive at George Washington University (

www.nsarchive.org).

The historic events of the night of November 9, 1989 came about from

accident and contingency, rather than conspiracy or strategy, according

to the

documents. Crowds of East Berliners, already conditioned by months of

refugee flights to the West and weeks of peaceful mass protests in

cities like

Leipzig, seized on media reports of immediate changes in travel

restrictions — based on a bumbled briefing by a Politburo member, Gunter

Schabowski — and

inundated the Wall's checkpoints demanding passage. Television

coverage of the first crossing that yielded to the self-fulfilling media

prophecy then

created a multiplier effect and more crowds came, ultimately to dance

on the Wall.

The documents show that the actual collapse of the Wall began with

Hungarian Communist reformers who proposed in early 1989 to open their

borders to the

West, while seeking particularly West German foreign investment to

solve Hungary's economic crisis. Hungarian Communist leaders checked in

with Soviet

general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev in March 1989, letting him know

they planned to take down the barbed wire; and Gorbachev — true to his

"common European

home" rhetoric — responded only that "we have a strict regime on our

borders, but we are also becoming more open." (

Document 1) The Hungarian decision sparked a stream

and then a flood of East German refugees.

Abandoned East German Trabants

line the streets of Prague.

Gorbachev himself unintentionally gave a signal that the Wall could

fall in his press conference on June 15, 1989 after a successful visit

to West Germany,

where in response to a question about the Wall, he said that "nothing

[was] permanent under the Moon" and connected German rapprochement to

the building of

the common European home. In fact, his conversations with Kohl and

other members of the West German government created a real breakthrough

in Soviet-FRG

relations, which would stand Kohl in good stead in the difficult

reunification talks during the next year (

Document 2).

Gorbachev especially reinforced the theme of

European unity in his speech to the European Parliament in Strasbourg

where he presented his vision of the common European home on July 7,

1989. After

speaking about an essentially united Europe based on universal human

values, it would be hard to argue in favor of its continued division.

By August 1989, the Hungarian-initiated refugee crisis had become so

acute that the West German embassy in Budapest had to shut down, unable

to handle the

hundreds of East Germans camped out there for visas. On August 19,

Hungarian reformers even hosted a "Pan-European picnic" near the

Austrian border, after

which some 300 East Germans high-tailed across the former Iron Curtain.

The subsequent negotiations on August 25, 1989 between Hungarian

Communist leaders

with West German chancellor Helmut Kohl and foreign minister

Hans-Dietrich Genscher show the Hungarian calculation that only the

deutschmark could save

them, and by mid-September the Hungarians lifted all East-West controls

(

Document 3).

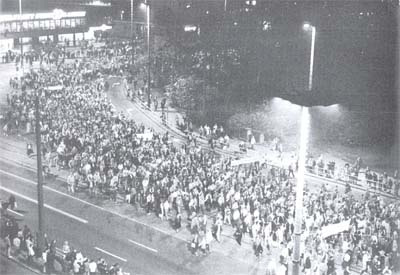

East German demonstrators take to the streets in Leipzig, October 9, 1989.

Other world leaders were not at all eager for the Wall to fall, notably

the British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, who told Gorbachev on

September 23 to

ignore those NATO communiqués about German unification, that even her

buddy, U.S. president George H. W. Bush opposed that kind of change (she

would

be wrong, when the time came. See

document 4).

As Gorbachev later commented to his Politburo on November 3, the West

did not want German unification, but it wanted to prevent it "with our

hands, to push us against the FRG" so as to head off any future

Soviet-German cooperation — but Gorbachev believed European integration

was

the ultimate solution to Soviet economic problems (

Document 6).

Czechoslovakia was closer to East Germany than Hungary was, and after

Hungary opened its gates, Prague quickly filled with East Germans

willing to dump

their Trabant cars in the streets for a chance to clamber over an

embassy wall and flee to the West. By November 8, Prague had become so

choked with East

Germans that the hard-line Czechoslovak Communist Party's Central

Committee made a demarche to East Berlin demanding they open their

borders — a moment of

pressure from fellow Communists that played a key role in the East

German party's decision to announce revised travel regulations the next

day (

Document 7).

The draft regulations were full of temporizing language and largely

intended to let off steam while kicking the emigrant problem down the

road. East

Germans would have to apply for visas, and the vast majority who

lacked passports would have to wait even longer for those. But the

presentation of the new

regulations came at the very end of a botched press conference from 6

to 7 p.m. Berlin time on

November 9

by SED Politburo member Gunter Schabowski, who did not know the

back story, the hedges, the limitations meant by the drafters of the

documents. Visibly rattled from the shouted questions about travel and

the Wall,

Schabowski read from his briefing papers the words "immediately,

without delay" when asked about the timing of the changes that would

allow any East German

to emigrate (

Document 9).

Television news and the wire services as well promptly announced the

opening of the borders, and in a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy

reinforced by TV

coverage, crowds of East Germans massed at the border crossings and

ultimately persuaded the senior official at the largest inner-city

checkpoint at

Bornholmer Strasse to open the gates (a story told in fresh detail by

Mary Elise Sarotte in her new book, The Collapse: The Accidental Opening of the Berlin Wall).

Once Bornholmer opened, other crossings soon followed; and within

hours, people were

chipping off souvenir fragments from the concrete panels formerly

surrounded by a "death strip" in which earlier Wall jumpers had died.

So unexpected was the Wall opening that Helmut Kohl himself was not

even in the country. Instead, the West German chancellor had gone to

Warsaw to meet the

new Solidarity leaders of that country, and work out some long-standing

Polish-German tensions. The transcript of Kohl's discussions with Lech

Walesa show

the Polish leader complaining that events in East Germany were simply

moving too fast, and even predicting, presciently, that the Wall would

fall in a week

or two — at which point Kohl would have no time (or money) for poor

Poland (

Document 8).

In Washington, the George H. W. Bush White House greeted the fall of

the Wall not with joy or triumphalism (that would come much later, when

the President

was running for re-election in 1992), but anxiety and even fear about

instability. When questioned by reporters why he did not show more

elation, President

Bush replied, "I am not an emotional kind of guy." (

Document 10)

Bush's caution and prudence were appreciated in Moscow, where

Gorbachev's messages to Kohl centered on preventing chaos and reducing

instability, keeping

"others within limits that are adequate for the time being…." (

Document 11)

But at Gorbachev's side, his foreign policy adviser Anatoly Chernyaev

in private let loose with one of the very few high-level expressions of

real joy

about the fall of the Berlin Wall. Chernyaev's diary entry for November

10, 1989 (

Document 12) contains the coda for the demise of the Iron Curtain, "the end of Yalta" and the

Stalinist system, and a good thing, about time, in Chernyaev's remarkable view.

![NEOCASTRISMO [Hacer click en la imagen]](http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_5jy0SZhMlaU/SsuPVOlq2NI/AAAAAAAAH1E/4xt2Bwd2reE/S150/ppo+saturno+jugando+con+sus+hijos.jpg)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario