The biggest change to the island’s economy isn’t the thaw in U.S.-Cuba relations

The end of Soviet subsidies in 1991 brought real economic desperation to Cuba. Dollars were traded on the black market. (In a dark Havana alley, I once got 125 pesos for a single greenback in a hurried transaction with a frightened man.) By 1994, in an effort to co-opt the black markets and once again take hold of the island’s resources, the government introduced the CUC. Initially this was strictly for tourists, the only legal tender for all those mojitos and langoustines. The CUC was pegged at 1:1 with the U.S. dollar, and just the commissions on exchanging it—up to 20 percent—earned the Cuban government billions a year.

This is the Cuban dilemma: Salaries are paid in ordinary pesos, and average just $20 a month, even though the cost of survival runs around $50 a month, and must be paid for with CUCs at government stores that, until now, accepted nothing else. As crazily inefficient as the existing two-currency system appears, it has allowed the government to maintain near-total dominance of the economy. The Cuban revolution has always viewed money as a problem, not a solution. That’s why the peso of the old republic had to be destroyed overnight in 1961. Having money let people be independent and operate outside the system. “It’s part of the DNA that Fidel imprinted on the revolution,” notes Ted Henken, a sociologist at Baruch College who has specialized in the island.

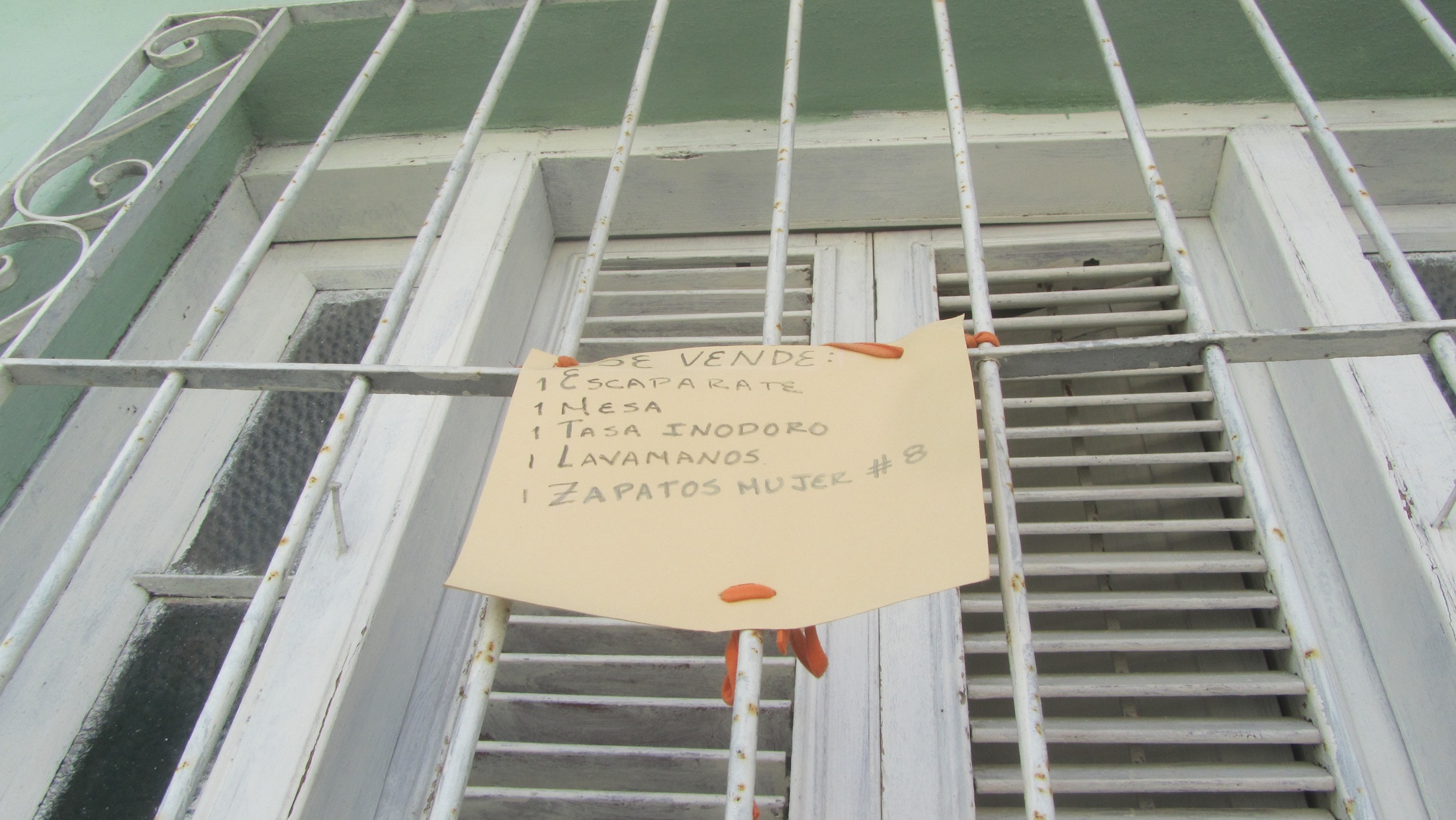

What the government has finally grasped is that the two-currency system has become economically and politically unsustainable. To get around it, Cubans steal state resources, work black market jobs, and even arbitrage the price differential between mangoes at opposite ends of the country. “Those in the peso-only economy are completely dependent on the government, which is in control of more than 85 percent of the total economy,” says John Kavulich, president of the U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council in New York. For the citizenry to “have a legitimate stake in the economy,” he notes, there should be one currency, used for salaries and all stores, and traded openly. “It needs to happen,” Kavulich says.

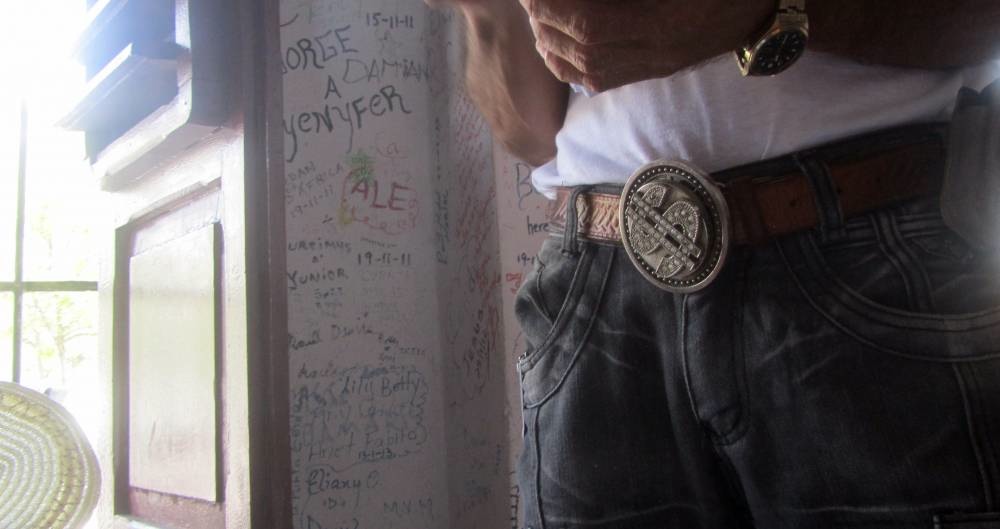

Havana today is in physical bloom. A gallon of paint costs 30 percent of a typical monthly salary, yet half the houses in the city seem freshly painted. The once-ubiquitous and fuming thunder chariots of old Detroit are either shined up with new chrome and paint or, more often, sidelined by more recent and reliable Korean and Chinese vehicles. The people I’d known on the edge of starvation over the last 20 years of visiting are now fighting the creep of their waistlines and the return of pastries and deep-fried everything at street-corner kiosks. Even in 1991, Cuba seemed more open than it was, an island without barbed wire or machine guns, the friendly blue ocean serving as its Berlin Wall. Now the openness is tangible: In December, Cuba and the U.S. announced that the two intend to reestablish relations after more than four decades of enmity. On Havana’s streets, there’s a charge of anticipation, and one senses a people eager to embrace the world.

He’s nonplussed about the currency change: “If you are running a business and doing well, you are going to do well with one currency or two. ... Honestly, I believe that anything you do efficiently and professionally is going to succeed in Cuba.”

Efficiency and professionalism require reversing decades of perverse Cuban incentives, however. Most waiters are state-trained and paid in worthless pesos: They often spend more time on break, or talking to friends in the street, than attending to diners. “They expect to have their job forever,” Alvarez says. “They get used to being bad.” So he hires blank slates: English-speaking college grads, many of whom have never seen the inside of a nice restaurant before. “The main thing,” Alvarez says, “is we want zero experience.”

He sounds optimistic. “Very,” he says. “There are over 250,000 entrepreneurs in Cuba since the new opportunities. … This is a door opening that isn’t going to close.”

If the opening has an official advocate, it’s Omar Everleny, the lead economist at the Center for the Study of the Cuban Economy. The center is in a onetime private residence in an elegant Havana neighborhood, surrounded by embassies. Despite arriving at the building with an appointment at 4 p.m., I find it empty; the next morning Everleny meets me in the library, amid the smell of decaying paper, to walk through the slow death of the CUC and the likely benefits for Cuba.

Everleny, like many Cubans, can recite the exact date economic reforms began: Sept. 9, 2010. Raúl Castro had assumed control in 2006, during his brother’s gastrointestinal illness. But his official promotion to leadership took two more years, and not till the fall of 2010 did he spell out reforms that expanded self-employment, removed limits on hiring by small businesses, and protected foreign investors from expropriation. Joint-venture hotels are routine now, with 60,000 rooms available. A new container port at Mariel, built by the Brazilian government, has created export capacity for a country that exports very little. More important, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff has gambled that pharmaceutical production and other tightly controlled businesses can thrive here.

Raúl Castro has meanwhile removed a series of prohibitions that infuriated Cubans: They can now own cell phones, buy and sell their houses, and even stay in the hard-currency hotels (817,000 did last year) that were once the symbol of foreign privilege. Raúl has also loosened, if not released, his grip on expression. Dissidents and regime opponents who were long blocked from leaving the country are now routinely seen at conferences in Miami, New York, and Brussels. In the 1970s, Cuba had some 15,000 political prisoners; today that number is between 50 and 60, according to the Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation.

The currency change is already happening, Everleny notes. Step one was to tell people, to prepare them psychologically for the coming transition. Step two, which began a week before my February arrival, was to roll out new, larger-denomination peso bills, so that people could pay higher prices without carrying a backpack.

The timing of the remaining three steps remains vague, in the Cuban way. Raúl had said in his speech that the two currencies had to be reconciled before the next Communist Party congress. That’s scheduled for April 16, 2016. The only thing known was that Day Zero would come before then.

Six hours of driving sweep me into the flat, colonnaded city. Many things are still as I remember them. The streets are sleepy, the bars bleak, and the local bus network consists of eight-person carts towed by horse. Yet even here there’s fresh paint, a computer repair business, and private furniture shops. I try to pay for ice cream with CUCs, making the woman laugh; the price is in pesos, 1/25th as much. The reverse happens at night, in the town’s best restaurant. Because everyone in the place is Cuban, I expect grim portions and pesos. But the shrimp are superb, a sommelier shows off a genuine wine cellar, and the Cubans all pay hard-currency prices, half a month’s salary on beer, beef, and watching baseball. In two decades of visiting, this is the first time I’ve shared a real restaurant with Cubans.

On the way back to Havana, I ride on a CUC bus. In the past, regular people had no choice but to ride peso buses that were scarce, slow, and crowded. For 23 CUCs I get a seat on a punctual express that fills up mainly with foreign tourists but also some Cubans, the kind who have more than an average month’s salary to spend on a bus ticket. We pass quickly through a string of grim cities—Colón, Cárdenas, Matanzas—all poor and unvarnished yet bustling with shops and commerce I’ve never seen before in Cuba. Like a vacuum, the unmet demand of Cubans is pulling reform to the farthest corners of the island.

The blogger Yoani Sanchez points out that this black market in information sticks to a familiar Cuban rule—nothing in el paquete should be explicitly political, to avoid drawing attention. But even the apolitical is subversive here, she says; when Cuban readers flock to lifestyle articles and glossy celebrity magazine covers, they’re imagining themselves in a different country. Everything they see in this digital realm—churros recipes, listicles on the secrets of entrepreneurial thinking—is part of a different state of mind, a terabyte of autonomy and desire.

Even though the economy looks better than at any time since 1991, Cuba remains deeply, dangerously reliant on Venezuela’s collapsing economy. The heirs of Hugo Chávez have kept the lights on in Havana by granting Cuba 100,000 barrels of oil a day at about half the market price. That effectively hides 45 percent of the island’s trade deficit. Venezuela also pays $5.5 billion a year for the almost 40,000 Cuban medical professionals who now make up half of its health-care personnel. Neither support can endure unchanged.

When MasterCard announced it would begin accepting charges from Cuba on March 1, the Cuban government slapped that down. U.S. airlines can now start flying directly to Cuba, or so Washington says—but there will likely be years of negotiations over safety, landing fees, and the reciprocal right of Cubana, a state-controlled, military-operated airline, to land its planes in Miami. The last thing on the Cuban list of reforms is sharing power. The Communist Party reflexively insists that nothing will change in Cuba, ever, but Obama’s rapprochement is certain to have an effect. Dissidents, the politically ambitious, and human-rights activists believe that some day they’ll be legally allowed to exist and their now-secretive work can become routine. The death of the CUC may turn out to be Day Zero for more than funny money.

![NEOCASTRISMO [Hacer click en la imagen]](http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_5jy0SZhMlaU/SsuPVOlq2NI/AAAAAAAAH1E/4xt2Bwd2reE/S150/ppo+saturno+jugando+con+sus+hijos.jpg)