By Megan O'Matz and Sally Kestin

The United States does not know how many fugitives are in Cuba.

Nobody

tracks it. Nobody even routinely asks for the return of those wanted on

serious federal charges, much less more common state offenses, the Sun

Sentinel has found.

Law enforcement officials on state and federal

levels say paperwork is rarely filed in Washington to request

diplomatic assistance out of a sense that doing so would be futile. The

United States has no working extradition treaty with Cuba.

"I

could request Mars send someone back and we'd probably have better luck"

said Ryan Stumphauzer, a former U.S. assistant state attorney in Miami

who prosecuted Medicare cheats, most of them Cuban-born. "We know Cuba

is not sending anybody back."

Since

President Obama's surprise shift in December toward normalizing

relations with the Communist-led nation, some members of Congress have

demanded that Cuba hand over fugitives. The irony: law enforcement isn't

regularly seeking their return.

Last week, three U.S. senators,

including Florida's Marco Rubio, asked the FBI to produce the names of

fugitives in Cuba and copies of their indictments. No complete list is

likely to be forthcoming.

There is no formal mechanism in use to

request extradition, no centrally collected records nationwide of how

many likely are on the run in Cuba, and no coordination among counties

or states on the issue, the Sun Sentinel has found.

Even in

Miami-Dade County, where most Cuban-Americans live, state prosecutors do

not log or tally fugitives thought to be in Cuba.

"It's not like

we send up to Justice our Christmas list of potential felons," said Ed

Griffith, spokesman for the Miami-Dade State Attorney's Office.

In

recent weeks the U.S. Marshals Office in South Florida has been

scrambling to compile a list of people possibly hiding in Cuba, in case

the Castro government suddenly agrees to expel such fugitives.

"We want to be prepared," said Marshals Office spokesman Barry Golden.

The

Sun Sentinel, in a recent far-reaching investigation into Cuban crime

rings in America, disclosed that Cuban nationals are taking advantage of

generous U.S. immigration laws to come to the U.S. and steal billions

from government programs and businesses.

Millions of dollars have

traveled back to Cuba, and many individuals flee there when police close

in on scams the Cubans specialize in. These typically involve health

care, auto insurance, or credit card fraud; cargo theft; or marijuana

trafficking, the Sun Sentinel found.

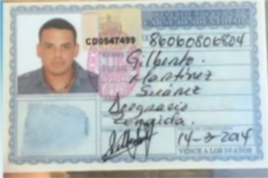

The Sun Sentinel located one

fugitive wanted in a million dollar Texas credit card fraud case living

in Santa Clara, Cuba. He'd written to the judge in his case in 2013,

saying he "went to the U.S. to steal" and included his return address in

Cuba.

Prosecutors

had no evidence he was actually in Cuba and had not sought his return.

"We can't extradite from Cuba. We wouldn't reach out to the State

Department in a case like that," said Scott Carpenter of the District

Attorney's Office in Fort Bend County, Texas.

In the occasional

diplomatic talks, high-level U.S. officials have brought up the issue of

fugitives in Cuba — usually the cases of prominent violent offenders,

such as New Jersey cop killer Joanne Chesimard, a member the militant

Black Liberation Army who fled to Cuba 30 years ago and was given

political asylum.

How these appeals happen are a mystery to most

street level investigators and prosecutors who simply don't bother

filing voluminous records to Washington because the process is

cumbersome, costly and likely fruitless.

"As

far as them putting together a package for extradition, I guarantee

that isn't happening," said Humberto Dominguez, a Miami criminal defense

lawyer. "It would be worse if they did: it would be such a waste of

taxpayer dollars."

Why send the paperwork to Cuba, he asked. "So they can utilize it as a bathroom implement?"

No answers or records

John

Caulfield, chief of the U.S. Interests Section in Havana until 2014,

said that for many years, American officials figured "there was no point

in talking to the Cubans" because they didn't expect any cooperation.

But

he said he'd tell individuals in law enforcement that if you don't ask,

you don't know what will happen. "We were surprised in some cases" when

the U.S. asked for someone's return and got it.

In the past

decade, Cuban officials have returned a handful of criminals:

Kidnappers. Child abusers. An insurance fraudster and others.

Neither

the Department of State nor the Department of Justice will answer

questions about how many fugitives the U.S. has sought to have returned,

who, or even whether, state and federal prosecutors request

extradition.

In recent months, the agencies have provided the Sun

Sentinel with the same prepared statement three times: "The United

States continues to seek the return from Cuba of fugitives from U.S.

justice, and repeatedly raises their cases with the Government of Cuba."

Said

Justice Department spokesman Peter Carr: "We generally do not disclose

if requests are made or provide information on whether specific cases

have been brought before different foreign authorities."

In March,

the Sun Sentinel filed a Freedom of Information request with the

Justice Department seeking copies of requests from prosecutors for the

return of Cuban nationals wanted for felonies since 2007. The newspaper

also sought records showing what efforts were made to inform Cuban

authorities or US diplomats in Cuba of a fugitive's possible presence in

Cuba.

The agency replied that it "failed to locate any responsive records."

The Sun Sentinel has received no records under a similar request made nine months ago to the State Department.

American

University Professor William LeoGrande, a specialist in Latin American

politics, said Cuba has had difficulty getting solid information from

the Justice Department on fugitives the U.S. wants. "I've had a Cuban

official tell me they couldn't even get confirmation that this was the

right person."

Teddy Roosevelt's treaty

It's

widely assumed that the U.S. has no extradition treaty with Cuba. In

fact, one was signed in 1904 under President Theodore Roosevelt. Its use

was suspended in the 1960s after Fidel Castro came to power.

"You

often hear that the extradition treaty between the U.S. and Cuba has

been abandoned. That's not so," said Robert Muse, a Washington attorney

and expert on Cuban-related law. "It's listed by the State Department as

a treaty in force. This agreement exists, it's just in abeyance."

Requesting extradition from any country is a long, formal, onerous effort, guided by the terms of each treaty.

Prosecutors

must assemble affidavits stating the facts of the case; texts of

relevant criminal statutes; certified copies of arrest warrants and

indictments; evidence such as court transcripts, photographs and

fingerprints of the criminal; and any conviction papers.

An

original and four copies must be sent to the Justice Department's Office

of International Affairs in Washington, which translates the material

and funnels it to the State Department. Prosecutors are warned not to

contact foreign countries directly.

Appeals are made by American Embassy officials through "diplomatic note," accompanied by the thick bundle of documents —certified and secured with an official seal and red ribbon.

Though

federal officials in Miami know that dozens of Medicare fraud fugitives

who stole millions fled to Cuba, "Why would the government file

extradition requests when there isn’t even a treaty to proceed under?”

said Stumphauzer, who left the U.S. Attorney's Office in Miami in 2011.

Asked

what federal agents do when they learn a Medicare fraudster has taken

off to Cuba, one current investigator explained: they throw up their

hands and say: "Oh crap," knowing the likelihood of recovering someone

is low.

State and local officials, too, make no attempts at extradition.

Miami-Dade

Police Sgt. Henry Sacramento, whose team repeatedly arrests Cubans in

marijuana grow houses, said: "We just put a warrant in the system and

hope they make a mistake in coming back into the country again."

"As far as extradition from Cuba," he said, "I don't know of anyone that's tried to do that."

Count unclear

The Jan. 23rd

letter Rubio and the two other senators sent to U.S. Attorney General

Eric Holder, requesting a list of all fugitives the FBI believes are

living in Cuba, notes "there is little definitive information about

their cases available publicly."

The senators wrote that there are

longtime murderers and airplane hijackers in Cuba, but also "numerous

others guilty of lesser but still important crimes, including money

laundering and health care fraud."

For years, members of Congress have accused Cuba of harboring 70 to 80 fugitives: most of whom fled there decades ago

More recently, the FBI in Miami has compiled a spreadsheet showing 20 Medicare fugitives thought to be hiding in Cuba.

The

Sun Sentinel, in its investigation, found references in court or police

records to an additional 50 wanted in other frauds, cargo theft or

marijuana trafficking.

The count could be far higher.

There

are 500 Cuban-born fugitives wanted on federal charges and at least

another 500 wanted on state charges in Florida alone. They could be

anywhere in the world, according to records provided by the U.S. Marshals Service and the Florida Department of Law Enforcement.

FDLE

does not require country of birth to be filled out consistently on

warrants, so it's impossible to fully determine exactly how many are

from Cuba or may have gone back there.

Proving a criminal is in

Cuba can be difficult. At times authorities know a fugitive boarded a

charter flight for Cuba, but in other cases they have only the word of a

family member to go on — and that person may lie to throw police off

the track.

"There's no method of confirming that somebody has

fled, either directly to Cuba or indirectly through another country,

because we don't have communication with anyone in Cuba to verify that,"

said Golden, the Marshals Service spokesman.

Some criminal defense lawyers representing Cuban offenders believe thousands of fugitives may have returned there.

Fort

Myers defense attorney Rene Suarez, who represents Cuban clients, said

public estimates of fugitives in Cuba are typically "big, federal type

cases."

"But most of these folks that have gone back, they're not

federal cases. The vast majority are just state charges that are tracked

county by county," he said.

Asked if there could be hundreds hiding in Cuba, he said: "No … there's got to be thousands of them."

Staff writer William E. Gibson and correspondent Tracey Eaton contributed to this report.

![NEOCASTRISMO [Hacer click en la imagen]](http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_5jy0SZhMlaU/SsuPVOlq2NI/AAAAAAAAH1E/4xt2Bwd2reE/S150/ppo+saturno+jugando+con+sus+hijos.jpg)