|

| allvoices.com |

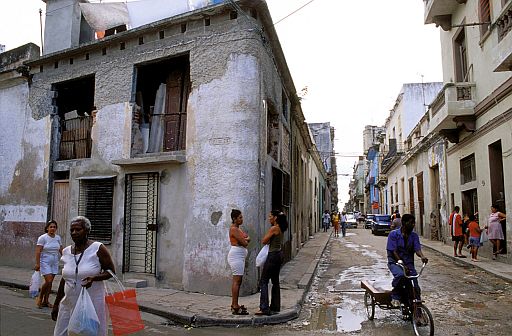

It was just a small sign, red, round and electrified, advertising

homemade pizza — the kind of thing no one would notice in New York or

Rome. But in Havana? It was mildly amazing.

Cuba,

after all, has been dominated for decades by an all-consuming

anticapitalist ideology, in which there were only three things promoted

on billboards, radio or TV: socialism, nationalism, and Fidel and

Raúl Castro.

The pizza sign hanging from a decaying colonial building here

represented the exact opposite — marketing, the public search for

private profit.

And it wasn’t just tossed out there. Unlike the cardboard efforts I’d

seen in the same poor neighborhood on a visit to Cuba last year, the

sign cost money. It was an investment. It was a clear signal that some

of Cuba’s new entrepreneurs — legalized by the government two years ago

in a desperate attempt to save the island’s economy — were adapting to

the logic of competition and capitalism.

But just how capitalist are Cubans these days? Are they embracing what

Friedrich Hayek described as the “self-organizing system of voluntary

cooperation,” or resisting?

“It’s a combination,” says Arturo López Levy, a former analyst with the

Cuban government now a lecturer at the University of Denver. “When more

people get more proactive and more assertive, then other people —

whether they like it or not — have to do the same. They have to compete.

I think that’s the dynamic.”

Indeed, like Iraq, Russia, Mexico or other countries that experienced

decades of dictatorial rule that eventually ended, Cuba today is a

society marked by years of abuse, divided and uncertain about its

future. The changes of the past few years — allowing for

self-employment, freer travel, and the buying and selling of homes and

cars — have been both remarkable and extremely limited. The reasons

small things like signs matter so much here is because everyone is

concerned with momentum, and no one seems to know whether Cuba is really

on the road to capitalism, as

The Economist

asserted in March, or if the island is destined to simply sputter

along, with restrained capitalism for a few and socialist subsistence

for the rest.

The debate is all the more complicated because the same leaders who

rejected capitalism for so long are now the ones trying to encourage

people to try it out. Raúl Castro was notoriously the revolution’s most

loyal Communist; now, as the country’s president, he is the main booster

for free market reforms. On one hand, a recent gathering of Cuba’s

Communist Party earlier this year included a session on overcoming

prejudices against entrepreneurs; on the other, Raúl Castro has said he

would “never permit the return of the capitalist system.”

“They are kind of schizophrenic,” says Ted Henken, a Cuba expert at

Baruch College. “They are saying they are changing, but they treat these

things as gifts and not as rights.”

And yet, there is no longer any denying that pockets of controlled

capitalism are emerging in Cuba. In Havana, in particular, small

businesses are everywhere. Entire urban industries, including taxis and

restaurants, are being transformed through a rush of new entrants, who

are increasing competition for customers, labor and materials. Even the

most elemental tasks that used to be managed by the state — such as

buying food — are increasingly in the hands of a private system that

sets its own prices based on supply and demand.

Though the initial burst of activity has slowed, some experts say the

explosion in commerce showed just how capitalist Cubans were all along.

Of the roughly 350,000 people licensed to be self-employed under the new

laws by the end of 2011, 67 percent had no prior job affiliation listed

— which most likely means they were running underground businesses that

then became legitimate.

Some of the most successful entrepreneurs are optimistic about Cuba’s

becoming more open to free market ideas. Héctor Higuera Martínez, 39,

the owner of Le Chansonnier, one of Havana’s finest restaurants (the

duck is practically Parisian), says that officials are “starting to

realize there is a reason to support private businesses.” He has given

people work, for example, and he brings in hard currency from

foreigners, including Americans.

“Before, we had nothing,” he said. “Now we have an opportunity.”

He is doing everything he can to make the most of it. When we met one

night at the restaurant, he had already written up several pages of

notes and charts explaining what his industry needed to grow — from

wholesale markets to improved transportation for farmers to an end to

the American trade embargo to changes in the Cuban tax code. In an

ingeniously cobbled-together kitchen, in which only one of three ovens

worked, he mostly seemed to salivate at the thought of vacuum packing so

his meals could be delivered more efficiently.

HE was about as capitalist as it gets. But will his ideas ever be

adopted? Like everyone else, he faces severe limits. He can hire no more

than 20 employees, for example. He does not have access to private bank

loans, and the government has shown little inclination to let people

like Mr. Higuera succeed on a grand scale.

Instead, when success arrives, the government seems to get nervous. This

past summer, officials shut down a thriving restaurant and cabaret

featuring opera and dance in what had been a vacant lot, charging the

owner with “personal enrichment” because he charged a $2 cover at the

door. A news article from Reuters had described it as Cuba’s largest

private business. A few days later, it was gone, along with 130 jobs.

The Castro government has tried to keep a lid on innovation in other

ways, too. It has not allowed professionals like lawyers and architects

to work for themselves. And its efforts at political repression have

focused over the past few years on innovative young people seeking space

for civil discourse in public and online — the blogger

Yoani Sánchez, or

Antonio Rodiles,

director of an independent project called Estado de Sats, who was

arrested in early November and released last week after 18 days in jail.

So for now, what Cuba has ended up with is handcuffed capitalism: highly

regulated competitive markets for low-skilled, small family businesses.

What economic freedom there is has mostly accrued to those whose main

ambition is making and selling pizza.

Which again raises the question: is Cuba really heading toward

capitalism or not? Skeptics are easy to find. “Every place in the world

that has had real change, it has changed because the regime itself has

allowed some significant openings and the door has been pushed wide

open,” says Senator Robert Menendez, Democrat of New Jersey. “That’s not

what’s happening here.”

Many Cubans say they are hesitant to let go of a reliable system summed

up by a common joke: “We pretend to work, they pretend to pay us.” Taxi

drivers told Mr. López Levy that they were working harder for less money

because of increased competition. A farmer I met at the wholesale

market outside Havana equated capitalism with higher prices, and said

that the government needed to intervene.

But mostly, this is an aging crowd and Mr. López Levy — who still has

friends and relatives in government — says that even among Cuban

bureaucrats, the mentality is changing. If so, more capitalism may be

inevitable. Because with every new entrepreneur it licenses, Cuba

becomes less socialist, less exceptional, less of a bearded rebel

raising its fist against the horrors of Yankee capitalism. In the eyes

of some Cubans, the jig is already up.

“The government has lost the ideological battle,” said Óscar Espinosa

Chepe, a state-trained economist who was sent to jail in 2003 for

criticizing the government. “The battle for ideas was the most important

battle, and they’ve lost.”

------------------------------------

Damien Cave is a New York Times correspondent based in Mexico City.

![NEOCASTRISMO [Hacer click en la imagen]](http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_5jy0SZhMlaU/SsuPVOlq2NI/AAAAAAAAH1E/4xt2Bwd2reE/S150/ppo+saturno+jugando+con+sus+hijos.jpg)