BOSTON -- In an ideal world, Yoenis Cespedes would be able to return to his country as other Latin American ballplayers do once the major league season is over.

Imagine

this. He would build his house in Campechuela, the town in the south of

Cuba where he was born. He would hang out with the two-year-old son he

left behind, catch up with his family and friends and get a hero's

welcome from Cuban baseball fans, known for the fervor with which they

follow the game. He would throw out the first pitch in the Cuban league

tournament, and why not? He would play in some games before returning

for spring training.

"If

I could do it, I would," Cespedes said. "Play here and enjoy myself in

Cuba, yes I would. I would spend time with my family and my friends.

I

don't regret the time that I lived in Cuba and I am not going to say

that I wish I had come here earlier, but I also don't regret the

decision I made. I am never going to regret having taken this step."

This

"step" is defecting from Cuba in the summer of 2011. For Cespedes, like

for the 30 or so other Cuban defectors expected to see action in the

majors at some point this season, there is no going back. Their world is

not that ideal.

As time passes, maybe Cespedes will

feel differently, maybe not. The Oakland A's, with whom Cespedes signed

a four-year, $36 million contract this past March, understood just how

mixed up his feelings would be this first year in the majors, and they

called up former A's pitcher Ariel Prieto from his minor league coaching assignment to mentor and interpret for their new outfielder.

Prieto left Cuba legally and was drafted by the A's in 1995, but he knows first-hand what kind of nostalgia Cespedes is feeling.

"It is a dream we all have," Prieto said. "I miss my

country and I would like to go there to see my friends. I know he would,

too. He would also love to be part of Cuban baseball. All this is part

of the adaptation process.

"Arriving here in the

United States is a shock for everyone. All of a sudden you are in the

big leagues. I came in the middle of the season and Yoenis came at the

start of spring training, but I know what he is going through in terms

of adaptation and I know it is not easy.

"He is

getting used to everything," Prieto said. "But the players are also

adjusting to him. They have made an incredible effort to make him feel

his best."

It has been less than a year since

Cespedes and his mother, former Cuban national softball team pitcher

Estela Milanes, left Cuba for the Dominican Republic via speedboat.

Cespedes said he would never have considered leaving Cuba had the

national team coaches recognized his talent, instead of leaving him on

the third-string team after he had just finished playing a dream season.

From

an economy that gives its citizens just enough to live, but no more,

Cespedes has moved into a world in which he has the economic means to

purchase almost anything he desires. So far, though, he has eschewed the

principal accoutrements of the nouveau riche. He is living in a rented

home in Oakland and says he has no immediate plans to make any major

purchases.

During

a half-hour pregame clubhouse interview last month at Fenway Park,

Cespedes answered questions in earnest, but without expressing much

emotion. Only the question about whether or not he had a car in Cuba

elicited a laugh.

"In Cuba, I didn't even have a bicycle," he said.

"I

am in no hurry to buy a car," he said. "With a car comes all kinds of

potential drama and my mind is focused only on playing baseball. After

the season finishes, I'll see whether I need one."

With

or without a car, Cespedes faces drastic changes. He has moved to a

country in which he does not speak the language, he is dealing with the

harsh reality that he cannot go home again, and he is playing in a

league with -- and against -- players he has never seen before. Soon,

there will come a time when he will have to deal with investments,

funding to help his family, payments on a home, electricity, cable,

water bills and such.

For now, Cespedes insists he

is tuning it all out, preferring to focus on his progress on the field.

He still calls his mother, who has made her home in the Dominican

Republic, every day. But otherwise, his singular focus is on the Oakland

A's and how to hit a Felix Hernandez fastball.

"He

can't be thinking about other things," Prieto said. "He is totally

focused on baseball, on being the best player possible and meeting the

high expectations that have been set for him. When the season is over,

he will think about a car and a home. But he will never stop calling his

family; that is part of who he is. And he needs that comfort, that

support and that love."

Adaptation 101

Everything

came fast at Cespedes after the A's signed him. His arrival in Arizona

for spring training took longer than expected because of problems with

the visa process, but he was able to convince Oakland manager Bob Melvin

that he was ready to play at the major league level, particularly for a

franchise undergoing a restructuring process.

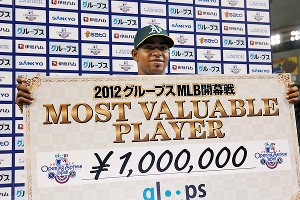

He

now bats fourth for the A's and is a key piece in their renovation

process. He hit a home run in his Cactus League debut. From there he

traveled with the team to Japan for its season-opening series against

Seattle, where he got his first hit, a double off the Mariners'

Hernandez in the first game. He hit his first major league home run the

next night. He has batted in a fifth of his team's runs so far this

season. He also met his idol, Manny Ramirez, and finished up the month of April playing in Fenway Park, the scene of some of Ramirez's best baseball moments.

His welcome into this new system also included a breach of contract claim

filed against him< by Edgar Mercedes, his former agent in the

Dominican Republic, where Cespedes lived before signing his major league

contract. News of the claim arrived as Cespedes was in Boston for the

A's series against the Red Sox, and he downplayed its significance.

"I have no opinion about that right now," Cespedes said. "I talked to Edgar by telephone. Those are Internet rumors."

Cespedes

closed out April hitting .250 with five home runs, 19 RBIs, a .319 OBP

and a .476 slugging percentage. The statistics are good, not great (an

OPS of .810 and three stolen bases), but they don't tell the whole story

about the man Baseball Prospectus considers the best Cuban player of

his generation, or the five-tool player we saw in the 2009 World

Baseball Classic. Melvin is trusting that this is all part of the

adjustment process on and off the field.

"Do you

know what? I am and I am not surprised," Melvin said. "I am surprised

based on how little exposure he has had, the short spring training and

the little or no knowledge of opposing pitchers. But I am not surprised

now that I know him as a person, how competitive he is and how well he

prepares every day. Each day he is looking to learn from the videos and

using all the resources he now has in the major leagues that he didn't

have before."

At the plate, adjustment has been a

little painful. During his first month, he had more strikeouts (24) than

hits (21), but Cespedes insists he usually starts his seasons slow and

heats up as the season goes along.

"Sometimes I rush

my swing because I am so anxious to play well," he said by way of

explaining his strikeouts. "In Cuba, the quality of the pitching is not

the same as it is here. There you might find one or two pitchers at 94

or 95 mph. Here, every day I find several and each pitcher who comes

along throws his hardest stuff. That's why I am working with [A's

hitting coach] Chili Davis to make the adjustment.

"In

Cuba, I would start the first two months hitting around .260 with three

or four home runs," he said. "After the first half of the season, I

would get hot and that's when I would have my best results. I hope that

it will be the same here. I am going to try to maintain my numbers

because I know that in the third month, I think … I am sure I am going

to hit even better."

So is Melvin, who has Cespedes signed through 2015.

"I

am really impressed with all the progress he has made in such a short

period of time," he said. "The best part is that we have yet to see what

he can really do."

Prior to last month's series against the Red Sox at Fenway, Oakland catcher Kurt Suzuki saw Cespedes wincing, and tested out his own Spanish in the clubhouse.

"¿Te duele?" ("Does it hurt?") asked Suzuki in Spanish. "¿Donde?" ("Where?")

Cespedes

pointed to his back and grimaced. Then he moved his arm to his back and

indicated the middle part to show his teammate where it was bothering

him. Suzuki tried to keep going in Spanish. He got stuck, but pointed to

the team's physical therapy room, where Cespedes could get help.

Major

league ballplayers and fans alike think nothing of a major league team

offering the resource of a trainer's room for players. But for Cespedes,

this, like the clubhouse luxuries and the team flights, is all new and

all part of his adaptation process. When he left Cuba, his only focus

was to advance his baseball career.

Estela's influence

Estela Milanes harbored a secret in her curveball, but only the coaches of the Cuban national softball team and Yoenis knew it.

"She

threw her curveball along the side of her arm," Cespedes said. "The

umpires never noticed but her coaches all knew that it was an illegal

pitch because she didn't throw underhanded, but rather side-armed her

pitches under her arm. It was not legal, but it was hard to notice. That

was her best pitch."

Cespedes never hit against his mom, but he had the misfortune of being on the receiving end of her curveball.

"One

day when I was really little, she asked me to catch for her and on one

of her pitchers she threw that curveball," he deadpanned. "Hit me right

in the face. I couldn't catch it."

Milanes, who

played on the Cuban softball team at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, never

threw any more curveballs to her son, but she is responsible for his

baseball career anyway. She sent him away from the family home in the

south of Cuba to attend a special baseball school, and she was the first

person he consulted when he contemplated leaving Cuba.

"She

taught me my love for baseball," he said. "From the time I was a kid

she took me everywhere with her. I grew up on the softball field. Every

day I would take my glove and my bat with me. When I was 10, she sent me

to a special school in Bayamo, about 62 miles [west] from home, so that

I would learn and develop as a player."

Although he

was Rookie of the Year in the Cuban league in 2003, Cespedes made a

name for himself outside of Cuba during the 2009 World Baseball Classic

when he hit .458 with two home runs, two doubles and three triples over

six games. The following year, he was co-leader in the Cuban league with

33 home runs, a league record. He finished that 2010 season hitting

.333 with a .424 on-base percentage, a .626 slugging percentage and 99

RBIs in 99 games.

All about respect

Born

in Campechuela, in the southern Granma province, Cespedes said it never

crossed his mind that he would seek a future outside of the country he

loved.

But in the summer of 2011, Cespedes says he

realized that if he wanted to advance his career, he would need to play

in the United States. Despite a stellar 2011 season, he had been

relegated to the third-string national team and he knew he would have

little chance of making the national team and playing in any big

international events.

"I

had a chance to play for the Cuban national team during the 2009 World

Baseball Classic, but at the time I never thought about leaving Cuba,"

he said. "I was just thinking that I could play at this level -- until

last year when I finished the league season leading in several

categories and they named three national teams and they sent me to the

lowest ranking one.

"The head coach told me they had

sent me to the lowest ranking team so I would have an opportunity to

play. The message I got was if they don't think I can play on the first

or second team, why was I going to keep playing baseball? Then I told my

mom that I wanted to leave Cuba and my mom followed my lead."

Cespedes

doesn't provide many details about the actual defection, but he and his

mother arrived in the Dominican Republic, where they established

residency. Cespedes knew that as a free agent, he had a shot at a

multimillion-dollar contract like fellow Cubans Aroldis Chapman, Alexei Ramirez and Kendrys Morales received before him.

It wasn't about the money, though. Rather, it's the respect. And the proof of that is in his off-field lifestyle.

"My

life has changed in many ways, both on an economic and personal level,"

he said. "All major league players are accorded the respect they

deserve. In Cuba, it was not that way. National team players were not

respected. The treatment was not adequate."

What

would have happened had Cespedes been given a spot on the first-string

team for Cuba? Would he be wearing red and white instead of the green

and white of the A's?

"Despite the situation in

Cuba, I had a chance to play on the national team; and compared to other

baseball players and other people in Cuba, I had the opportunity to

live at a level that was not very high class but in the middle. I had

the possibility to live well there, but with much more difficulties,

things that aren't a factor here," he said.

"Now,

little by little, I will look for a way to do something with my money so

it lasts. I have my financial advisers and I will look for a way to

invest soon, not so much for profit, but so that I can save some."

So

all seems to be as well as can be expected for Cespedes. While he

learns to live with abundance, he is also learning to hit off pitchers

such as Hernandez, the Rangers' Yu Darvish and the Yankees' CC Sabathia. Life might even be perfect if he could just catch a flight home to Campechuela at the end of the season.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario