|

| Finca Vigía/ en.wikipedia.org |

|

| Ernest and Mary Hemingway at their Cuban farmhouse, Finca Vigía. Photograph: Popperfoto/Getty Images |

The

mystery of whether Ernest Hemingway’s widow volunteered or was coerced

into leaving their Cuban house to the nation has come a step closer to

being solved, with the discovery of a letter in which she states that

her late husband “would be pleased” that Finca Vigía be “given to the

people of Cuba … as a centre for opportunities for wider education and research”.

Hemingway lived on the 19th-century Cuban farm for 21 years, between

1939 and 1961, writing his masterpieces The Old Man and the Sea and For

Whom the Bell Tolls there as well as posthumously published works

including A Moveable Feast and Islands in the Stream. He committed suicide in Idaho in 1961.

The property became a museum in 1962, but it has been unclear whether

this was following the wishes of Mary Hemingway, his fourth wife, or at

the insistence of the Cuban government, with differing accounts from

different parties.

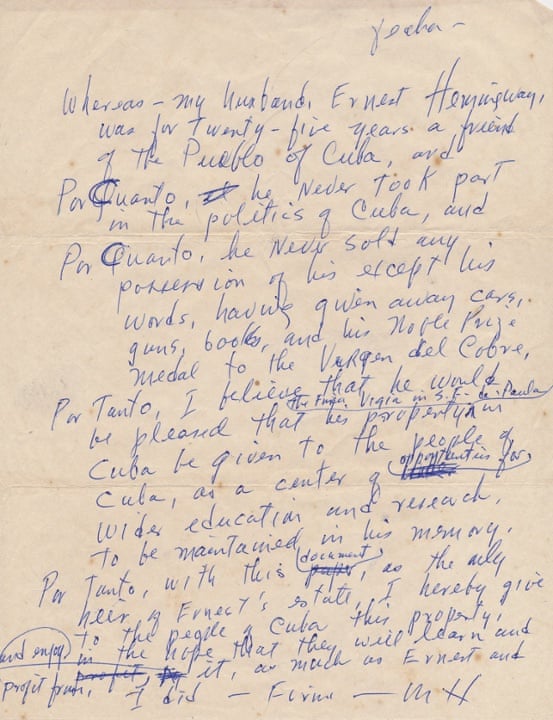

The newly discovered letter,

dated 25 August 1961, sees Mary Hemingway specifically donate the Finca

Vigía to the Cuban people. “…Whereas – my husband, Ernest Hemingway,

was for twenty-five years a friend of the Pueblo of Cuba … he never took

part in the politics of Cuba … he never sold any possessions of his,

except his words, having given away cars, guns, books and his Nobel

prize medal to the Virgen del Cobre,” she wrote to her husband’s friend

Roberto Herrera.

“I believe that he would be pleased that his property … in Cuba be

given to the people of Cuba … as a center for opportunities for wider

education and research, to be maintained in his memory. With this

document, as the only heir of Ernest’s estate, I hereby give to the

people of Cuba this property, in the hope that they will learn and

profit from, and enjoy it, as much as Ernest and I did.”

Sold this week via Alexander Historical Auctions, the letter was

found among the papers of Herrera. “Ernest Hemingway had committed

suicide in Ketchum less than two months earlier. However, at some point

shortly thereafter, Mary backtracked and stated that after Hemingway’s

suicide, the Cuban government contacted her in Idaho and announced that

it intended to expropriate the house, along with all real property in

Cuba. These documents show that Mary did indeed intend to donate the

home to the Cuban people,” said the auction house in its catalogue. The

handwritten note was snapped up on Wednesday for $1,100 (£716), a price

well below the estimate of $2,000-$3,000.

Valerie Hemingway – who was Ernest’s secretary before marrying his

youngest son, whom she met at the author’s funeral – went to Finca Vigía

with Mary shortly after Hemingway’s death to sort through his papers.

She said via email that “what is being auctioned is a draft of a memo

Mary intended to give to [Fidel] Castro that Roberto Herrera was going

to translate. As far as I can remember Mary never actually sent the

memo; she gave the draft to Roberto afterwards.”

Her own memoir, Running with the Bulls: My Years with the Hemingways,

sees Valerie write that Mary “genuinely wanted to see her husband’s

memory endure by creating a shrine of the home he loved and dedicating

it to the Cuban people, among whom he had lived for more than a third of

his life … Mary’s first idea was that the finca would become a learning

centre, and to that end she wanted to leave there as complete a record

of her husband’s life and most especially of his work as was prudent.”

But Naomi Wood, author of the novel Mrs Hemingway,

said that Mary Hemingway’s own memoir suggests the situation was not

quite as straightforward. “The question is whether the Hemingway house

was ‘donated’ by Mary, or coerced from her, or extracted from her via

diplomacy. In all likelihood it was a mixture of all three,” she said.

“In her memoir, How It Was, she uses the words ‘acquisition’ and

‘appropriation’, which suggests the takeover of Hemingway’s property was

done with some unwillingness on her part, rather than a donation as the

auctioned letter suggests. Though the auctioned letter suggests a

donation, her memoir suggests bullying, though Castro does it in the

most gentlemanly fashion, even asking her: ‘Why don’t you stay here with

us in Cuba?’”

Mary

Hemingway recounts a telephone conversation from the time in How it

Was, in which she says to a Cuban official that “I’m not sure if I wish

to give you our finca. [They could appropriate it, of course, as they

had done to so much US property there.] Perhaps your government would

give me permission to go down to remove our personal papers. Would you

find out and call me back tomorrow? This same hour? Muy bien.”

She was advised, she writes, “to take the chance of recovering

Ernest’s manuscripts, if nothing more. By this time United States

citizens were prohibited journeys to Cuba, but the US immigration

authorities in Miami gave me the exit and re-entry permits.”

The author’s widow would bring back crates of papers on a shrimp boat

travelling from Havana to Tampa. “Mary also recounts her negotiations

with Castro to remove a few paintings back to the US: including a Paul

Klee and Juan Gris,” said Wood. “She also manages to remove Hemingway’s

wax-sealed manuscripts they’d found at the Banco Nacional. Mary’s cargo

left on a shrimp boat back to Tampa, which was the last to have any

clearance papers from the US. More importantly for scholars than the

nature of the deal for the Finca Vigía donation or appropriation was the

fact that she managed to get those manuscripts out.”

Dr Susan Beegel, editor emerita of The Hemingway Review, said the discovery of the letter – first covered in Fine Books & Collections – was “new and interesting”.

“It’s nice to see her thoughts on how she intended the people of Cuba

to enjoy the museum – still thriving today,” said Beegal. “It’s

well-known that Mary deeded the Finca Vigía to the people of Cuba. After

the Castro revolution, the house could have been appropriated, as was

the case with other US property in Cuba, but instead the Cuban

government approached Mary to request the house as a gift, to be used as

a monument to Hemingway. She negotiated with them (and the Kennedy

administration as well, because US citizens were not allowed to visit

Cuba) to be able to return and remove personal belongings, art, and

Hemingway’s manuscripts from the house in exchange for the donation.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario