From

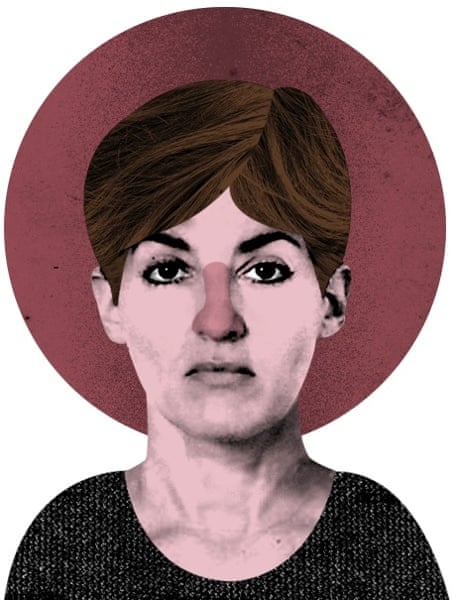

a maximum-security prison in Texas, former United States military

analyst Ana Montes has been offering up bumper-sticker justifications

for why she betrayed her country and spied on behalf of the Cuban

government over the course of 17 years. “I believe that the morality of

espionage is relative,” Montes wrote in a private letter to a friend

last year. “The activity always betrays someone, and some observers will

think that it is justified and others not, in every case.”

Montes had no idea how prophetic her words would be. While the

57-year-old American citizen remains locked up as one of the most

damaging spies in US history, the Cuban-born spy who led

American investigators to Montes was set free to worldwide applause last

week, during a landmark thaw in US-Cuban relations. Several news

outlets have since identified the Cuban double-agent as Rolando Sarraff Trujillo,

and multiple US officials I’ve interviewed this past week have

described him as a cryptographer whose code-breaking secrets have been

the gift that keeps on giving to the CIA, NSA and FBI.

I have been following the Montes case for more than a decade, and profiled Montes and her family for the Washington Post Magazine

last year. Despite extensive interviews with the officials who pursued

her – and even access to a secret CIA profile of Montes – I never

learned of the existence of the Cuban code geek who helped bring her

down. On Wednesday, President Obama broke the news, hailing the Cuban

double-agent as “one of the most important intelligence agents that the United States has ever had in Cuba”.

As I retraced the colliding paths of these dueling spies, a senior

Obama administration official revealed to me on Friday that the Cubans

had never requested the release of Ana Montes – not a single time over 18 months of secret prisoner-swap negotiations.

The once-revered Pentagon analyst known as the “Queen of Cuba” had been

left behind, a fitting betrayal for a woman who made a career out of

duplicity and deceit.

By the time Montes attended graduate school at the

Johns Hopkins University in the early 1980s, her anti-authoritarian

worldview was fully baked. It didn’t take long for her to meet a

like-minded student who seemed eager for a friend. The gregarious grad

student was, in fact, a Cuban talent scout who wanted “to facilitate the

recruitment of Montes to serve as an agent of the Cuban Intelligence

Service,” prosecutors divulged last year.

In 1985, Montes would find herself on a clandestine trip to Cuba

for operational training, and before long she had found work with the

Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the Pentagon’s major producer of

foreign military intelligence. The Cubans “tried to appeal to my

conviction that what I was doing was right,” Montes would later admit to

investigators, in the first of many naïve assumptions that would come

back to haunt her.

For the next 16 years, Montes feverishly worked two jobs, her star

rising in Washington and Havana. By day she was a whip-smart analyst for

the DIA. At night, she re-typed every top-secret document she could

remember onto a Toshiba laptop provided by the Cuban intelligence

service. Soon she was briefing the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the

National Security Council, and won a certificate of distinction from

then-CIA Director George Tenet.

All the while, Montes was meeting handlers in Washington-area Chinese

restaurants, and artfully slipping in and out of Cuba to debrief the

island’s intelligence officers. As Cuban-American relations stalled, the

Soviet-trained masters of deception taught Montes how to pass packages

to agents innocuously, beat the lie detector and, importantly, retrieve

coded messages in the privacy of her DC apartment.

Montes got her orders the Cold War way: through numeric messages transmitted anonymously over shortwave radio. Tres-cero-uno-cero-siete, dos-cuatro-seis-dos-cuatro,

a haunting female voice would drone on into the night, cutting through

the otherworldly static. Montes would key the digits into her laptop,

and a Cuban-installed decryption program would convert the numbers into

Spanish-language text.

It was a code almost from another universe, practically begging to be broken by an enemy not that far away.

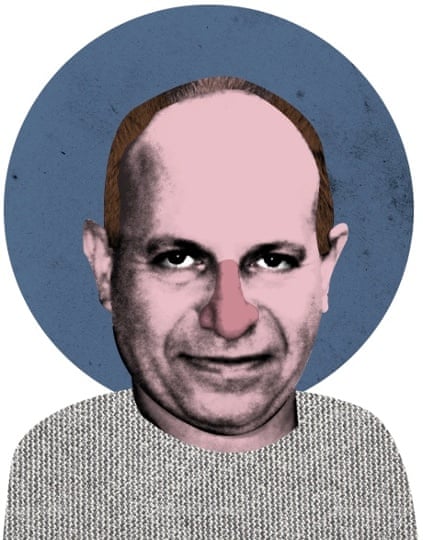

More than 1,000 miles south in Cuba, Rolando Sarraff

Trujillo was making a name for himself, too. After graduating in 1990

from the University of Havana, the handsome father of one – known to

friends as “Roly” – began work for Cuba’s Directorate of Intelligence

(DI). According to an online biography

posted by his family, Sarraff Trujillo was employed as a lowly

journalist assisting the intelligence directorate. In reality, he was a

skilled cryptographer helping to encrypt messages to and from Cuba’s

far-flung network of spies, said Chris Simmons, a former chief of a

Cuban counterintelligence unit in the DIA who helped investigate Montes.

“He worked on agent communications,” Simmons told me.

But Roly Sarraff Trujillo did more than that – he was a one-man

intelligence goldmine. As a cryptographer, Sarraff Trujillo understood

precisely how Cuba communicated with agents in the field, chiefly

through the same “numbers station” broadcasts that Montes picked up

night after night on her store-bought Sony radio. “He gave up how the

Cubans transmitted HF [high frequency] broadcasts,” Simmons said. “He

revealed communications shortfalls” that the CIA could take advantage of.

As a backroom comms guy, Sarraff Trujillo likely did not know the

true identities of the Americans working on Havana’s behalf, Montes

included. But the technical data and mastery of Cuban cryptography keys

that Sarraff Trujillo imparted to the CIA would guide and even

supercharge Americans investigators’ efforts for more than a decade –

inextricably linking him with his polar opposite in espionage, even as

he helped to out her.

“It’s like a time-lapse photo ... a gradual process,” said one

current US intelligence official of Sarraff Trujillo’s codebreaking

breakthroughs.

Another US official with knowledge of the case told me that Sarraff

Trujillo and two Cuban defectors working for the CIA provided computer

records straight from Cuba’s Directorate of Intelligence. “That data is a

treasure trove of information about Cuban intelligence,” the second

official told me.

From the records, the CIA was able to deduce how many agents the

Cubans were running, their rough geographical locations and the command

structure of the DI. Now American investigators knew where to look, and

how to decipher encrypted messages sent to illegal agents hiding in the

US.

US intelligence officials refuse to confirm or deny if Sarraff Trujillo is, in fact, the mystery Cuban released last week in exchange for three Cuban spies held in the United States along with, in a separate deal announced on the same morning as the expanded diplomatic relations, the imprisoned American contractor Alan Gross.

Sarraff Trujillo’s sister, Vilma, declined comment in an email, as did

spokespeople for the CIA, National Security Council and Director of

National Intelligence (DNI).

But the DNI gave clues to Sarraff Trujillo’s identity by revealing on Wednesday that the man “has spent nearly 20 years in a Cuban prison due to his efforts on behalf of the United States”.

The Cubans arrested Trujillo in November 1995, on espionage charges,

meaning he’s been imprisoned for the last 19 years. US officials have

told the New York Times, the Associated Press and other media outlets

that Sarraff Trujillo was indeed the CIA’s man in Havana. “I know of

all the Cubans on the list of people in jail and he is the only one who

fits the description” of the unnamed asset in question, Simmons told Newsweek on Wednesday. “I am 99.9% sure that Roly is the guy.”

In the years following Sarraff Trujillo’s arrest,

American investigators began to methodically work their way towards

Montes. Ironically, it was Ana’s own sister, Lucy, who would play a key

role in helping the FBI identify and capture the Queen of Cuba.

It began with a Cuban spy ring based in Florida. More than a dozen

members strong, the so-called Wasp Network was infiltrating Cuban exile

organizations and US military

sites in Florida. Armed with Sarraff Trujillo’s intelligence and aided

by other tipsters, American officials were able to pinpoint key Wasp

conspirators. The FBI’s Miami field office began searching their homes

surreptitiously and uncovered secret “crypto keys” on their laptops that

deciphered ongoing communications with Havana, a US official familiar

with the case told me.

The Cubans were supposed to change the crypto codes every six months,

the official said, to minimize security risks. But they got careless.

“The Cubans fucked up. They occasionally used the crypto keys more than

once,” the official said.

By applying the crypto keys to older coded shortwave transmissions that the NSA

routinely recorded, the FBI began to build a profile of a senior US

official who was aiding the Cubans. FBI special agents now knew that

their “UNSUB” – or unidentified subject – had high-level access to US

intelligence on Cuba and had purchased a specific type of Toshiba laptop

to communicate with Havana.

It was 1998, and Lucy Montes was working in Miami as an FBI language

analyst who translated wiretaps and other sensitive communications. The

FBI called on her to translate hours of wiretapped conversations of the

Wasp spies. Although Ana presumably would have been proud to learn that

her sister had helped expose a Cuban spy ring, Lucy knew from years of

frustrating trial and error that Ana refused to discuss her career.

Ever. Lucy never even brought it up.

With the Wasp arrests, Ana’s handlers pulled back and assessed the

fallout. Ana was alone, and she was scared – with good reason.

By September 2000, Chris Simmons learned from a fellow intelligence

officer that the FBI was having difficulty identifying an UNSUB spying

for the Cubans. Simmons shared the tip with Scott Carmichael, a “mole

hunter” whose job it was to ferret our spies and other security risks

within the DIA. Carmichael and a colleague began inputting some of the

FBI’s closely held clues into their employee databases. After scanning

through a hundred possible employee matches, a name popped up. Except

this name came from deep within the bureaucracy: ANA BELEN MONTES.

Following months of investigative scrutiny, the FBI put a tail on

Montes. They videotaped her making suspicious calls on pay phones, even

though she carried a cellphone. They gained access to her banking

accounts, through the use of a national security letter, and learned

that Montes had applied for a line of credit in 1996 at CompUSA. Her

purchase? The same model of Toshiba laptop that had been referenced in

the coded Cuban communications that Sarraff Trujillo knew so much about.

Once FBI black-bag operatives searched Montes’s apartment and

discovered a Sony shortwave radio and Toshiba laptop, it was all over.

The hard drive, which Montes had tried to wipe clean, included

instructions on how to translate Cuban high-frequency broadcasts. One

file mentioned the true last name of a US intelligence officer operating

undercover in Cuba. Montes had revealed the agent’s identity, and her

Cuban intelligence officer thanked her in writing: “We were waiting here

for him with open arms.”

After pleading guilty to espionage, Montes told her

CIA debriefers she felt she had a duty to protect Cuba from its neighbor

up north. “All the world is one country,” she said. “In such a

world-country, the principle of loving one’s neighbor as much as oneself

seems to me to be the essential guide to harmonious relations.”

But despite last week’s détente between the United States and Cuba,

it’s hard to imagine that the events Montes and Sarraff Trujillo set

into motion more than two decades ago will amount to any kind of lasting

harmony. One current US intelligence official predicted last week, as the White House was declaring a man who sounded a lot like Roly Sarraff Trujillo “a legitimate hero”,

that the opening of embassies in Havana and Washington will simply make

spying more convenient – with each nation’s spies more abundant and

easier to follow.

“You still have an intelligence service, and we still have an

intelligence service,” he told me. “It won’t be a sudden change of heart

for either side.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario